2007 Gandhi Jayanti Lecture

Topic: Religion, Violence & Gandhi

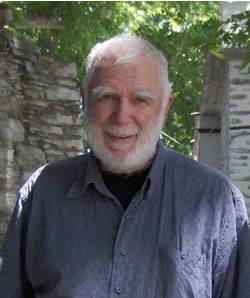

Author: Dr. Paul Younger, Emeritus Professor of Religion, McMaster Unversity

A talk given to the Mahatma Gandhi Society Ottawa, at Kailash Mital Theatre, Carleton University, Sept 29, 2007

“Religion, Violence & Gandhi”

by Dr. Paul Younger

Gandhi is often pictured as a saint who taught people how to live non-violently. I prefer to picture him as a political analyst who figured out what the nature of violence was and how one might deal with it. In this paper, I try to fill in some of the gaps between his day and ours, and explore what I think his insights might be on the forms of religious life and the nature of the violence we now see around us.

Gandhi was born into a traditional religious atmosphere. As he remembered it, at the time he wrote his autobiography in his fifties, the most significant feature of that religious setting was that it had great variety. His father and mother had very different religious practices. His father was personally illiterate in that he could not read religious texts, but he took great care to have both Hindu and Jain texts read to him by scholars. His mother was uninterested in those text readings, but she went to a number of temples and daily to a temple that had Hindu, Jain and Muslim symbols. She also took great care to keep a great many fasts that she had learned about from other women. Gandhi was well aware that there were myths of violence in Hindu religious texts, but he interpreted them mythologically and did not think of them as prescriptions for current behaviour. He especially tried to understand the teachings of the Bhagavad Gita on virtues such as courage and discipline and how they affected one’s actions, but he assumed the highest religious form was the pursuit of Truth or the highest Self or Atman.

The Colonial Period

Only very gradually did it dawn on Gandhi that the understanding of religion inherent in the British colonial officials’ behaviour was very different from his own. Actually he had a warning in this regard when as a child he was told by a Christian preacher on the street corner of his town that he would go to hell if he did not change his identity and become a “Christian”. The experience had shocked him, but when he went to England at age nineteen, he found the lower class landladies of England much like his mother in their dedicated and traditional religious practice. In that context, he was happy to attend church with them and to read the Bible they offered him. He even tried to continue this practice in South Africa, but there he was usually engaging colonial authorities, and they confronted him over and over with their idea that they were at the pinnacle of “civilization,” and that Christianity was the underlying religious form of that civilization. The violent backside of that colonial arrangement was to make clear to him that only a fool would speak of “Indian civilization” or would imagine that he had the same rights as an Englishman. Colonial authorities were expected to “orientalize” or caricature the quaint local forms of religion, and they had the authority to use violence and throw colonized people off the train, as they did Gandhi, if they challenged the ideas associated with the British understanding of “civilization”.

By 1910 Gandhi was sure he had understood this colonial argument aright, and on a journey back to South Africa from Britain he wrote the small book entitled Hind Swaraj . In this little book he wrote a devastating critique of this colonial view. His main burden was to mock the notion that any group would have a monopoly on “civilization”, but he also went on to point out some of the moral flaws British civilization had fallen into and to answer some of the critiques of Indian civilization that had been offered. Having made these points, he then went on to attack “Hindu leaders” who he accused of having adopted the same framework of thought in that they were willing to use violence to establish the superiority of “Hinduism”. In the book, Gandhi referred only to “Hindu leaders” but scholars now know that Gandhi spend much of his time on that visit to London with V.D. Sarvarkar who would later found the Hindu Mahasabha in order to provide political support for the Hindu tradition and who became a strong advocate of the use of violence.

When Gandhi returned to India, he continued to have to clarify why he took such exception to the Colonial way of linking religion and empire. The most common situation in which his position was misunderstood was the consistent position he took that Christian missions were a part of this colonial pattern. People wondered how he could object to the social work missionaries did when it was often similar to the social work he himself advocated, but he realized that in some ways it was missionaries especially who subscribed to the proposition that they alone represented true civilization and that Hindus belonged to a culture of uncivilized “darkness”. Gandhi was clear that this was not the message of traditional Christian practice but of a modified religious message associated with the violent structure of empire. Consistent with his opposition to Christian missions was his unease about the reverse missionary movement of Hindus like Swami Vivekananda who claimed a higher civilizational position for India because of its spiritual superiority. Swami Vivekananda had made this claim in 1892 at the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago, and at the time, Gandhi was just returning from his studies in England so there was never a confrontation between the two, and, in any case, Vivekananda’s whimsical claim was not directly supported by military force. In any case, Gandhi was thorough and adamant in his objection to the way in which imperialism twisted the role of religion and allowed it to be associated with cultural conflict and violence.

The Post-Colonial Era

Gandhi lived most of his life under colonial rule and is associated in most people’s minds with India’s long struggle for liberation from colonial rule. He is, however, today also spoken of as a pioneer in post-colonial studies because he was so deeply concerned about what would happen at the end of the colonial era. In looking forward to the post-colonial era, he saw once again that religion was being modified to serve political ends. What alarmed him was that in this context religion was reduced to communalism, and traditional practice and ethical norms were set aside if it served the political interests of the self appointed community leaders. In the seemingly noble name of seeking a “homeland”, ethnic conflict was almost inevitable and the especially ugly forms of ethnic and racial violence were likely to break out.

Gandhi was particularly saddened by the early development of the Jewish quest for a homeland in what was called at the time the Zionist Movement. Early in the last century many people were sympathetic when Jewish religious leaders reflected on their years of unhappiness within European society and began to wonder if their religious practice would not have been easier if they had maintained their homeland in Palestine. What many did not notice when there was so much talk of shifting borders in the area associated with the collapse of the Ottoman empire was that the Zionists assumed it was alright to use violence to take some of the Palestinian territory. When Gandhi heard about some of the first violence in the 1930s he wrote a careful letter to the great Jewish theologian, Martin Buber, arguing that the use of violence was not justified and expressing the hope that the Zionists could somehow share the territory with the Palestinian peasants. Buber wrote back vehemently defending his position and ignoring Gandhi’s advice. We now know that the initial violence in Palestine has led to a spiral of violence that continues, and that the Palestinian violence now seems to be drawing larger and larger areas within its powerful orbit.

The place where most outside observers thought the communal violence would be most severe was in the Indian subcontinent where 20% Muslims, 5%Sikhs and 5% Christians would have to somehow live with 70% Hindus. Gandhi argued furiously that even to pose the problem in that communal way was wrong and that a variety of religious life was a blessing to any society. Jinnah, who declared himself a Muslim leader, was the exact opposite of Gandhi in that he had no roots in traditional religious practice and did not even support the Muslim version of the imperialist use of religion, which had been present in the medieval Muslim empires and continued in a broken way in the new dreams of either a renewed Caliphate or a unified Arab state. He had a brazenly cynical view and acknowledged that he was interested in religion as something that could be manipulated to create a unified social unit and therefore a powerful state. The violent breakup of his original Pakistan state makes clear how fragile the idea of using religion as a basis for defining statehood really is. The Sikh quest for a homeland of Khalistan followed closely the quest for religiously based statehood initiated by Jinnah. Because the Sikh community was much smaller than the Muslim, the methods of communal organization were somewhat more effective and the variety in the traditional religious practice disappeared more completely under what was called the Singh Sabha reforms. As a result, although the Sikh state was never formed, what we see in the case of Sikhism is both a more complete transformation of religion to a communal form and a number of very intense experiences of violence. While Gandhi’s fierce opposition to the development of communal religious forms cost him his life, post-colonial India clung to the hope that he was right and that it was not necessary to redesign religion in a communal mode in order to develop a strong and stable social order.

The post-colonial era was a confusing one because it seemed to be a time of liberation and secularism, and yet it saw religion recycled as communalism and saw it lead to a good many examples of ethnic conflict and bitter violence. The colonial era had seen traditional religion transformed to serve a political master, but there had at least been a touch of nobility in the role religion had been given in defining the civilization the empire proposed. In the post-colonial era, the task religion was given was to create a communal consciousness, and in many contexts that actually took away individual freedom and even destroyed the rich traditions of religious practice. It should be said that in many situations post-colonial societies did not move in a communal direction, and that some liberated societies realized early on that there were major differences in the religious backgrounds of their members and decided that they would encourage religious variety to continue. In some cases they found that the sharing of traditions that this variety involved was a cultural stimulus and that interesting forms of hybridity emerged on their own. Guyana, Trinidad and South Africa might be cited as examples where keeping the variety alive proved especially creative, and Sri Lanka might be cited as an example of a place where that strategy was badly needed but was not tried.

The Era of Globalization

The issues that characterize the era we now live in are too close to us to be easily defined. Many people use the term “globalization” to describe the general characteristics of the era and that seems a reasonable term with which to begin. Some of the features of this era are at least benign and a few have changed our lives in wonderful ways. To cite those that are closest to my personal experience, I do not know what I would have done without the multi-cultural revolution that has flooded into Canadian cities and universities during the past generation. And if the “Incredible India” adds are correct, I take it that the poverty of India I experienced first hand fifty years ago is a thing of the past.

What I guess no one would have expected to see mixed in with these exciting changes is the sense of “homelessness” that haunts so many people in this globalized world. I just said positive things about the way in which Guyana and Trinidad used the openness of post-colonial society to achieve new forms of cultural hybridity, but it was in a book of poetry by Canadian Caribbean authors that I first heard about this new sense of “homelessness”. To state the problem as they do “when you belong to three cultures you belong to none”. Or, to take a much more painful example, the CBC documentary this week about the life of the Sikh boy, who just a year ago took his guns to Dawson College to do violence to his classmates and himself, tells a very personal story of how “homelessness”affects someone.

What makes the media feel that, in a globalized world, it is responsible for defining the meaning of events? And what makes it determined to find a religious meaning behind the flood of random violence that characterizes our time? Let me focus on three examples of violence that came to my attention this past week. 1. Once again Osama bin Laden sent a video to us to remind us of the events of September 11, 2001. He did appear a bit like Jesus teaching the masses and he did suggest that the West should turn to Islam. 2. A friend reminded me of the event some years back now when a woman named Tenmoli Rajaratnam made her way from Sri Lanka to India and pushed through a crowd so that she could touch the feet of Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi before blowing them both up. He was reminding me of this event because she is now considered a kind of goddess and is revered by thousands of pilgrims in a temple. 3. And this week thousands of Buddhist monks in Myanmar (Burma) have left their meditation and begun marching on the streets as cell phone imagery of the event is flashed around the world in the vain hope that the globalized world will have some way to overthrow the generals who rule their country.

There are, of course, many features in these examples of contemporary violence that are unique to that example, but I place them before you together in order that we might focus on the general characteristics. In all three instances, we have individuals that feel alienated by the emergence of the global society, and in that sense are expressing their “homelessness”, but they are immediately alienated by the nation-state to which they are attached and want to express their bitterness in violent action. What is peculiar about their action is that it is “random” in that it is unrelated to any personal or political goal, but it is filled with symbolic meaning by the eager media that provides these actors with an ancient religious identity in the absence of a meaningful personal or political one. Neither the individual actors nor the military regimes that they do battle with are traditional practitioners of religion, nor do they utilize the colonially modified form of religion or the communal form of religion characteristic of the post-colonial era. Religious symbols used in this context are randomly chosen ways of referring to a pre-modern era before the present forms of community and state were set in place, and as such they imply a radical alternative to contemporary society and imply that religious symbols support the use of violence against that society.

If my analysis of contemporary forms of violence, and its entanglement with religious symbols, is on the right track, then what we are witnessing is a third stage in the trend Gandhi so lamented where religion is reinterpreted to explain a new political situation. Colonial violence could be cold and brutal, as Gandhi knew, but it at least thought it had a religious purpose in its origin. Post-colonial ethnic violence had a very specific religious purpose in the narrow perspective of the community that wanted to provide its people with a homeland, but its violence quickly became an end in itself and today brings wave after wave of violence back into the lives of those communities. Globalized random violence is a product produced for the global media by alienated individuals, and has absolutely no purpose in the lives of those nearest to the actors, except perhaps to visit on them further violence. In all three instances, “religion” is dragged into the story to give a misleading meaning to the brutal acts of individuals, but the facade is shallower and shallower in each case. The last case makes it almost impossible for those who follow traditional religious practices within their normal social structures to provide any account of the distorted use of their symbols that the media digs out of the wreckage of violence.

Is there an alternative to this disquieting story of how religion is dragged into every new manifestation of violence? How did Gandhi deal with what he considered the political distortions of religion he saw in his own day? What he did essentially was to go in the exact opposite direction we are going in when we allow the media to interpret events for us. The media thrives on violence, but then it desperately tries to overcome the randomness it made feasible in the first place. When it plays up some distant religious symbols associated with the actor’s identity it gets us all hopelessly entangled in political games about our own identity. Gandhi focused not on the violence, but on the Truth to which every human being is drawn. Gandhi understood human nature to be essentially good. People on their own outgrow their infant urges to gratify their five senses and express themselves in violence, and they gradually develop an emotional life, a mental life, a personal character, and sometimes a full spiritual life and sense of the universal good. Traditional religious practices of all sorts help this natural process along, but religion that is distorted to serve political purposes stops this development and invites personal crises and political dreams to express themselves in violence.

The good news is that people and societies wake up when the meaninglessness of violence dawns on them. Rwanda went through the worst experience of violence anyone in our generation has heard of, but it has found its way back, and this week announced that it will soon be the first country where every citizen has a computer and a cell phone. Sixty years ago India was reeling from the fears surrounding de-colonization and the shooting of Mahatma Gandhi. Today things are better. The brutal oppression in Myanmar today is hard to watch, but there are those who are saying their prayers and imagining a peace beyond the violence, and we will hold hands with them some day.

In coming here today to celebrate Gandhi’s birth and reflect on his vision you are affirming that you will patiently pursue his quest for Truth. I am happy to be able to share with you in that pursuit.

About the Speaker:

Dr. Paul Younger was first introduced to the Gandhian technique of Non-violent Action by a group of Afro-American women when as a teenager he offered to help challenge the rioting in Trenton, New Jersey. After studies in Banaras, India and Princeton, New Jersey he came to McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario in 1964. He has written eight books including most recently:

Dr. Paul Younger was first introduced to the Gandhian technique of Non-violent Action by a group of Afro-American women when as a teenager he offered to help challenge the rioting in Trenton, New Jersey. After studies in Banaras, India and Princeton, New Jersey he came to McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario in 1964. He has written eight books including most recently:

The Home of Dancing Sivan – The Traditions of the Hindu Temple in Citamparam, Oxford 1995, and

- Playing Host to Deity – Festival Religion in the South Indian Tradition, Oxford 2002.

Synopsis of the Speech:

Newspaper readers have come to expect to see `Religion` and `Violence` linked together. Stories of terrorist bombings, oppression of women, and threats of one nation against another are regularly èxplained` by a superficial reference to sectarian or religious differences.

Gandhi grew up in a colonial era when a `Christian` empire ruled his homeland, and he spent his formative years in South Africa where his sensitive post-colonial mentality recognized that Muslim, Hindu and Christian Indians would have to live with an African majority.

What he recognized is that linking religion and communalism in the way people were starting to in his day was to misuse the category of `religion`. What he offered to do was to share his own experience of religion or èxperimenting with Truth` and show how that led him to Non-violent Action.

Is it too late to learn from Gandhi the true meaning of the category of `religion`?